Whose Work is Reconciliation?

Hello readers! Welcome back. In the last post, we discussed land acknowledgements. Many non-Indigenous peoples see land acknowledgements as one small step towards reconciliation. But what is reconciliation? What does it actually mean? These are the issues I want to talk about today, with a particular focus on residential schools and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Given Canada’s real history , it’s not Indigenous peoples who are responsible for reconciliation.

As I was doing research for this post, reading articles and accounts and looking through pictures, I had a hard time. Residential schools are hard for me to research and talk about. It’s something I wish simply hadn’t happened. But it did. And even though it’s hard, we have to understand the pain and harm residential schools caused in order to make sure it never happens again. I’ve decided that even if it’s hard to learn about, I can’t stop learning. I hope you decide the same thing. Take a break if you need to but don’t pretend these events didn’t happen. That only continues to erase and ignore Indigenous history, which is the opposite of reconciliation.

Before we begin learning about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we first need to learn about residential schools.

What were residential schools?

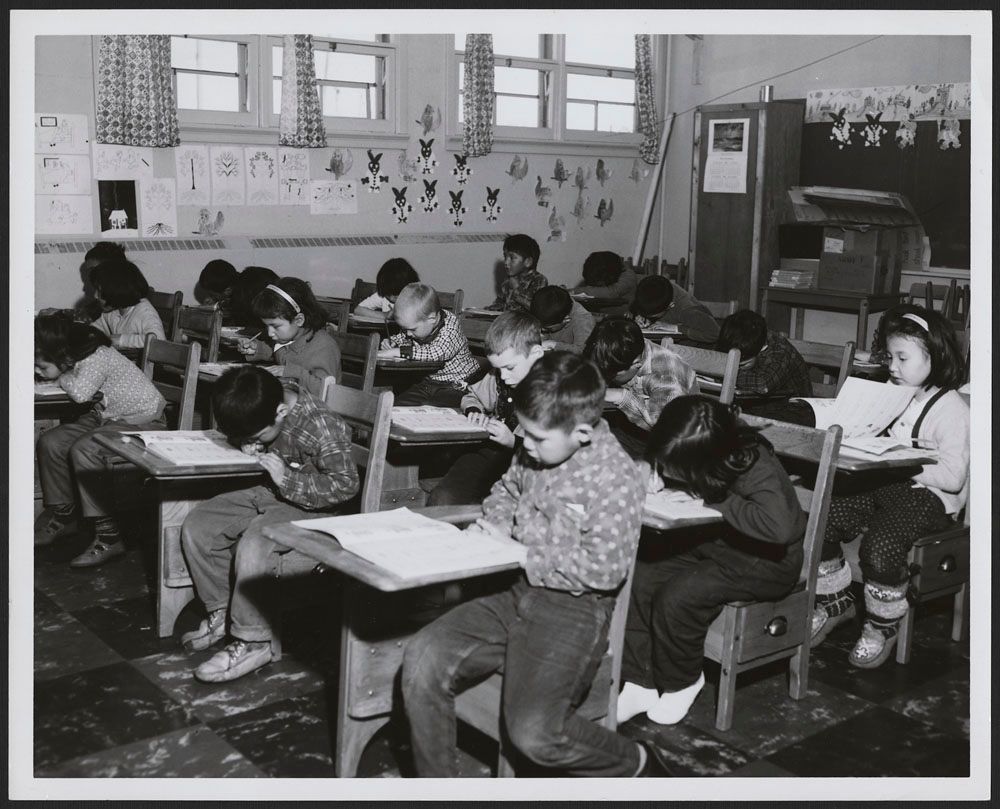

Residential schools were instituted by the government of Canada in 1876, although the Mohawk Institute was the first to operate in 1831. In 1879 Prime Minister Sir John A. MacDonald commissioned Nicholas Flood Davin’s Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds in which Davin stated, “If anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him very young. The children must be kept constantly within the circle of civilized conditions.”

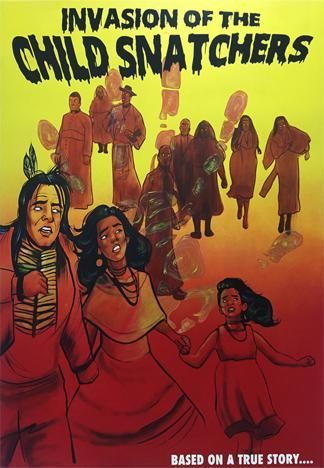

Residential schools were the government’s response to the continued expansion of European settlers across Canada and the increasing demand to clear the way for new settlers. The aim of residential schools was to erase Indigenous cultures, which would make taking Indigenous lands easier, through the assimilation of Indigenous peoples into the dominate white, British and French cultures.

Assimilation, the government decided, began with stealing Indigenous children from their communities and their families. Residential schools were based on Victorian poor houses combined with religious schools and prisons. Most schools were run by Catholic and other Christian churches. Converting the children to Christianity was a core component of assimilation.

When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.

Sir John A. MacDonald, Prime Minister of Canada, addressing the House of Commons, 1883

In 1920 the Indian Act was amended to make school attendance mandatory for all Indigenous children under 15. Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs and a known assimilation extremist who advocated heavily for the residential school system, stated “I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone . . . Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.”

The Residential School system stole 150,000 Indigenous, Métis, and Inuit children from their families between the 1870s and the 1990s. Some children were as young as two years old when they were ripped from their homes and made to live away from their parents and families. Their clothes and personal belongings were taken away and their hair was cut short. They weren’t allowed to sing or dance or speak in their native languages and were forced to use English. If they were caught speaking in their languages the punishment was swift and severe.

That’s already horrible in itself. But it could get even worse when the nuns and priests of the school inflicted abuse onto their students. Many children had to suffer through mental, physical, and sexual abuse at the hands of residential school staff.

They put a big chunk, and they put it in my mouth, and the principal, she put it in my mouth, and she said, “Eat it, eat it,” and she just showed me what to do. She told me to swallow it. And she put her hand in front of my mouth, so I was chewing and chewing, and I had to swallow it, so I swallowed it, and then I had to open my mouth to show that I had swallowed it. And at the end, I understood, and she told me, “That’s a dirty language, that’s the devil that speaks in your mouth, so we had to wash it because it’s dirty.” So, every day I spent at the residential school, I was treated badly. I was almost slaughtered.

Pierrette Benjamin, survivor of La Tuque Residential School, Survivors Speak , Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Read the full report here

Because of the horrifying conditions of these schools the kids often rebelled. Kids would run away, if they were caught they would be punished. Kids would fight back and be punished. Kids even got together and planned to burn the school buildings down but even then new ones would be built and they would still be forced to attend.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimates that between 4000 and 6000 children died in residential schools from malnutrition, lack of medical care, and disease. This number is considered conservative by many since records were often destroyed, went missing, or were simply not kept. It also ignores the children forced into Federal Indian Day Schools, who faced the same abuses. The last residential school in Canada closed in Saskatchewan in 1996. That was only 25 years ago.

Hear from Residential School Survivors

Watch Stolen Children | Residential School Survivors Speak Out on CBC to learn how residential schools affected survivors, their children, and grandchildren.

Watch: The Stranger

“The Stranger” is the first full chapter and song of The Secret Path. Adapted from Gord Downie’s album and Jeff Lemire’s graphic novel, The Secret Path chronicles the heartbreaking story of Chanie Wenjack’s residential school experience and subsequent death as he escapes and attempts to walk 600 km home to his family.

Watch: Voices from Here: Wes FineDay

In this condensed life history, Wes FineDay, Nehiyaw Knowledge Keeper, discusses his resistance to colonial violence and his lifelong work and extensive knowledge of medicines, oral history, and ceremony.

Find which residential school was closest to you and when it closed with this interactive map. Click here to access the map .

Most came back from residential school feeling broken. They didn’t know who they were anymore with their traditions forcibly taken away. At the same time, they still didn’t fit into white Canadian society. They suffered all of that hurt for so many years that they didn’t know how to process. They didn’t understand why. What did they do to have been put through that?

As time went by one of the hardest things has to be that the rest of Canada had no idea about this state-sanctioned abuse, no concept of this attempted genocide, and have continued on like things were normal. How could the abuse of 150,000 children be considered normal? A lot of the general public still doesn’t understand what a residential school was, the atrocities committed in these schools, and the impact this system has today. This is not right.

Again I want to emphasize that a mere 25 years ago, in 1996, the last residential school closed in Marieval, Saskatchewan.

“Imagine your community with no children.”

Tara Williamson

Singer-Songwriter and researcher, Tara Williamson explains the ’60s Scoop and the current apprehension of Indigenous children known as the Millenial Scoop.

After years of activism and organizing, in 1991 the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was created and became one of the earliest Canadian government documents that sought to make reparations for the wrongs done to Indigenous peoples. In 2006 the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement was passed so that the Canadian government would financially compensate all residential school survivors. Money is not enough though, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was also formed in 2008 as part of the settlement.

- Read more in: More than $3B paid to 28,000 victims of residential school abuse: report here

In 2009 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) began its plan to listen to and document survivors’ testimonies. The Commission also gathered testimonies from victims’ families, knowledge keepers, and Indigenous communities. They wanted all those affected to have a say in how the trauma of residential schooling should be handled in the present and future.

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

From the Truth and Reconciliation Commission came the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation , which houses all of the testimonies and related documents from the TRC.

92 Calls to Action

Survivors want this history to be remembered and acknowledged. Among the many reports and materials produced by the TRC, the 92 Calls to Action are something I believe all Canadians should read. It lists 92 ways to bring change to Canada and work towards a reconciliation between Indigenous people and settlers.

Reconciliation is no easy task. Indigenous people want everyone in Canada to understand the pain and damage of residential schools, how our futures were ruined and how the pain is still hard to talk or even think about today. The government needs to keep and fulfill its promises made to Indigenous peoples and listen to their voice. I want you to learn more, I want you to read the calls to action and I want you to take action. Now.

What is Reconciliation?

In this web series called “First Things First,” Indigenous experts take a look at what it really means to reconcile after generations of systemic racism against Indigenous peoples.

Click below to download and read the 92 Call to Actions.

Watch: Namwayut: We Are All One. Truth and Reconciliation in Canada

Chief Robert Joseph shares his experience as a residential school survivor and the importance of truth and reconciliation in Canada.

Next, we’ll look at land sovereignty. Though it may seem distant, it too is related to reconciliation, treaties, and other previous blog subjects. Land sovereignty is actually one way to reconcile problems with the colonial government. We will get more into what land sovereignty means and what it could look like.

Read the next post: Land Sovereignty Now

About the Author

Mnawaate Gordon-Corbiere is Grouse clan and a member of M’Chigeeng First Nation. She is Ojibwe and Cree. Born in Toronto and raised in M’Chigeeng, in 2019 she obtained her BA in History and English from the University of Toronto.

Since graduation, she has been working in the heritage sector with a focus on Indigenous history. Her most recent project was working as a co-editor for the historical anthology Indigenous Toronto: Stories that Carry This Place

released in spring 2021.

About Built on Genocide

Built on Genocide is a large-scale installation by multidisciplinary artist Jay Soule | CHIPPEWAR, reflecting the events and policies throughout Canada’s history that have deliberately undermined and destroyed Indigenous livelihoods.

The work is influenced by the mass genocide of the buffalo as a result of the colonial railway expansion. The buffalo decimation is an underacknowledged but foundational aspect of “Canadian” history, with consequences that persist today. Built on Genocide will address the direct correlation between the genocide of the buffalo and the genocide of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

© 2025 Luminato Festival Toronto, All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy

|

Terms and Conditions