Honour the Treaties

Hello again! Mnawaate welcoming you back for a little more real Indigenous history of Canada. Last week we looked at the effects of European contact

on the Indigenous population in North America. This was a period of rapid change for Indigenous peoples. Over time, as Europeans decided to settle here

, land agreements in the form of treaties needed to be made. That’s what we’ll talk about today.

You have probably heard of treaties but can you name which treaty you’re living within right now? When I think about treaties made with European colonists sometimes all that comes to mind is how Indigenous peoples were increasingly cheated by the treaties. Over time more and more was lost: land, fishing and hunting, even clean water. All the “rights” treaties were supposed to protect were, and are, frequently infringed upon.

Dismissal and dishonouring of treaties is just one of many ways that the genocide of Indigenous peoples was brought about.

What I think about the most when it comes to treaties is that many of the agreements within them were simply not upheld. I think this stems from fundamental differences between Indigenous and colonist relations to land. Indigenous peoples saw land as something precious that needs to be cared for and respected in order to receive the gifts it offers. European colonists saw land as something they could exploit for profit and manipulate however they chose. These different perspectives on land, and the ongoing dishonouring of the treaties, continue to cause conflict today. In this post, we’ll look at land agreement treaties and how treaty relations between Indigenous nations and the British Crown deteriorated over time.

But I’m getting a bit ahead of myself here. Let’s start off simple by covering what a treaty is.

What is a Treaty?

What is a treaty? A treaty is an agreement made between two or more parties that are continually reviewed and renewed. Both parties are present when the agreement is initially made and both sides are meant to fully understand what they are agreeing to and what the other side expects of them. They can be made between Indigenous nations or, as was later the case, between European powers and Indigenous nations. Treaties are not just land-based but can detail peace agreements, alliances, or any serious issue between groups that needed settling. Though you may know treaties mainly as agreements between Indigenous nations and colonial powers, there were many treaties before Europeans came along.

Learn More about Treaties

If you live or work within Toronto, you may already be familiar with the Dish with One Spoon treaty, which covers Toronto and beyond. The treaty was made in 1701 between the Anishinaabek and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (which includes the Kanien’kehá:ka, Onondaga, Oneida, Tuscarora, Seneca, and Cayuga), who were long-time enemies that often disputed over territory.

Prior to the Dish with One Spoon treaty, Anishinaabek nations came together to gain back the territory north of Lake Ontario they had lost to the Haudenosaunee previously. The Anishinaabek and Haudenosaunee battled until they were able to reach an agreement. To end their disputes, the two opposing nations came to an agreement on how they would share the land. They vowed to treat the land like a dish that they ate from with one shared spoon, meaning that they all shared the land’s resources like plants, animals, and water together and made sure there was still enough left for everyone.

The Dish with One Spoon treaty was recorded mnemonically in a wampum belt, with a dish holding a spoon at the centre of it. The wampum belt was made of highly valuable whelk and quahog shells that required care, demonstrating the careful nurturing needed to maintain the treaty. Though not all treaties were made with a wampum belt, the Dish with One Spoon wampum belt helped solidify the treaty by providing a physical representation.

This is just one example of many treaties between Indigenous nations. After a treaty was made it was important to renew the treaties every few years. The nations would gather and each side would express their understanding of the agreement, including terms that needed to be upheld, in front of the other(s). This way both sides knew their responsibilities and had a clear understanding of their agreement.

Watch: Learn about Dish with One Spoon Wampum with Rick Hill Sr.

- Read more about Wampum by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy here

Treaties with Europeans were different. Most significantly, these treaties were not wampum belts but signed papers. Additionally, Europeans viewed land as something to be bought, owned, captured, won, or taken over, which were new concepts to Indigenous peoples. As more settlers came to the continent, they wanted land of their own to use; they either bought it illegally or squatted. Indigenous nations, not surprisingly, had a problem with settlers squatting on their lands without asking permission or negotiating treaties. Indigenous nations and the British Crown decided to regulate land agreements through the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

Is Canada Built on Genocide ?

Built on Genocide is a large-scale installation by multidisciplinary Indigenous artist Jay Soule | CHIPPEWAR , reflecting the historical events and colonial policies throughout Canada’s history that have deliberately undermined and destroyed Indigenous livelihoods.

Running September 22 – October 24, 2021 at Harbourfront Centre.

To deal with this escalating issue, and to claim title to North America following the 7 Years War with France, in 1763 the British Crown issued The Royal Proclamation. The proclamation granted ownership of North America to England’s King George III while also stating that all land was under Indigenous title until ceded by treaty to the British Crown. Under the Royal Proclamation all treaties had to meet the following criteria to be considered valid:

- Treaties could only be negotiated between Indigenous nations and the British Crown,

- Only the Crown could purchase land from Indigenous nations and sell that land to settlers,

- Both parties (Indigenous and government) had to be present at the treaty signing,

- There had to be consent between the two parties,

- Indigenous nations had to be compensated for all lands and resources taken.

You’re likely thinking so what’s wrong with The Royal Proclamation ? Good question.

The first issue is with its design and authorship. The British colonizers wrote The Royal Proclamation with zero input from the Indigenous nations whose land the Crown was claiming a monopoly over. The second issue is with the treaty-making process, which often ignored the regulations laid out in 1763.

Watch: Trick or Treaty by Alanis Obomsawin on the NFB

Enlightening as it is entertaining, Trick or Treaty? succinctly and powerfully portrays one community’s attempts to enforce their treaty rights and protect their lands, while also revealing the complexities of contemporary treaty agreements.

Trick or Treaty? made history as the first film by an Indigenous filmmaker to be part of the Masters section at TIFF when it screened there in 2014.

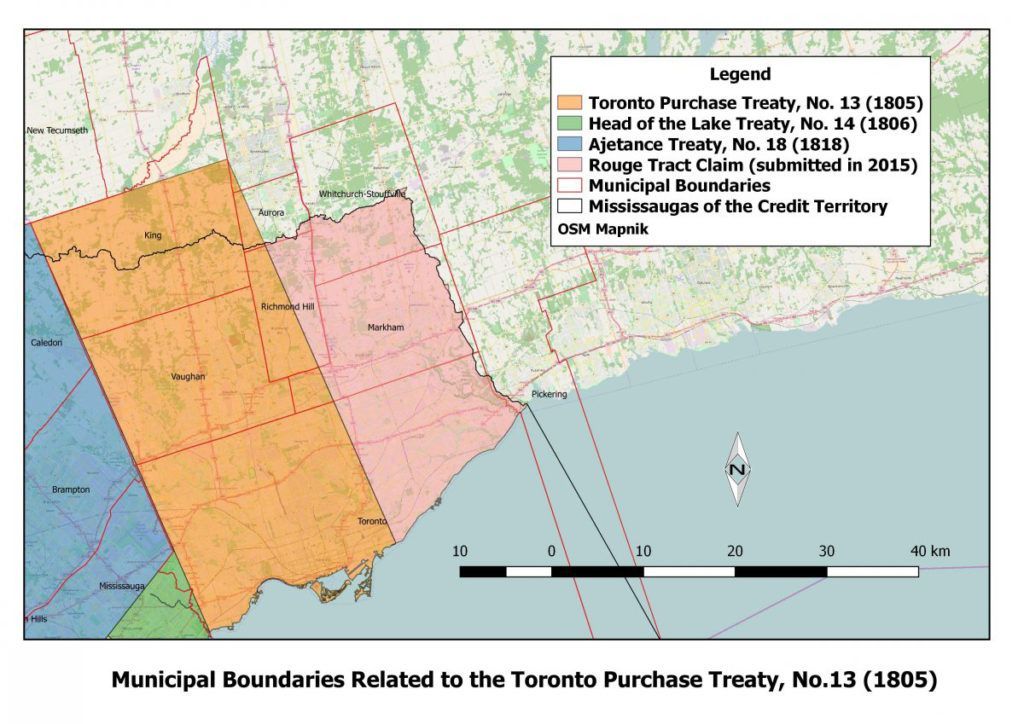

Let’s look at the Toronto Purchase of 1805 as just one example of treaties “signed” under suspect conditions. In 1787, Sir John Johnston, Superintendent General of the Indian Department, met with the Mississaugas of the Credit who, it was claimed, sold 10 square miles of land in the Toronto Purchase Treaty. However, when the deed of sale was examined years later it was blank, there was no description of the lands sold to the Crown, and the marks of the chiefs were made on separate pieces of paper attached to the blank deed.

Unsurprisingly, local Crown administrators started to doubt that the treaty was legal, which meant that York (Toronto), not to mention the homesteads of many settlers, were on unceded land. In 1805, a new Toronto Purchase Treaty was signed. This time the Crown purchased 250, 830 acres of land, which was, unbeknownst to the Mississaugas chiefs negotiating this new treaty, roughly double what was negotiated in 1787. How much did it cost? 10 shillings. That’s roughly $33.33 today.

This is just one example of how colonial officials often found ways to twist the rules of the Royal Proclamation so they could get the most out of the treaties without the Indigenous party realizing it.

Treaties began to change in 1818 when the Treasury of Britain found it could no longer support the expense of treaties and left it in the hands of colonial officials instead. As these colonial officials did not have as much money as Britain, it was decided they could instead pay in perpetuity rather than a lump sum. On the Indigenous side, this was accepted because they were glad to know future generations would be secured.

Watch: A Sacred Trust

Learn more in this video from Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation

- Find the treaty you are on with this map from Native Land

- Read different treaty texts dating from the mid 1700’s to the early 1900’s here

Colonial acquisition of land accelerated after 1818. Reserve lands that provided Indigenous nations somewhere to settle quickly became necessary. Oftentimes reserve lands were retracted as settler demand grew and nations were pushed out of their traditional territories. Many Indigenous nations cared primarily about preserving their hunting and fishing rights that nearby settlers often hindered. In some areas land remained unceded, meaning it was never purchased by the Crown, and other times separate treaties overlapped the same area.

I’ve heard Indigenous people tell others to read our treaties. Some may wonder why we must read such an old document and why it matters today. If you take a look at treaties, they are meant to be continually renewed and maintained, over time this has stopped. All of us in Canada have a part to play in the treaty we live on but many of us don’t know it. These treaties show us that this land is Indigenous land and that we all have responsibilities if we want to share it together. Dismissal and dishonouring of treaties is just one of many ways that the genocide of Indigenous peoples was brought about.

Read the next post: Land Acknowledgements and Land Back

About the Author

Mnawaate Gordon-Corbiere is Grouse clan and a member of M’Chigeeng First Nation. She is Ojibwe and Cree. Born in Toronto and raised in M’Chigeeng, in 2019 she obtained her BA in History and English from the University of Toronto.

Since graduation, she has been working in the heritage sector with a focus on Indigenous history. Her most recent project was working as a co-editor for the historical anthology Indigenous Toronto: Stories that Carry This Place

released in spring 2021.

About Built on Genocide

Built on Genocide is a large-scale installation by multidisciplinary artist Jay Soule | CHIPPEWAR, reflecting the events and policies throughout Canada’s history that have deliberately undermined and destroyed Indigenous livelihoods.

The work is influenced by the mass genocide of the buffalo as a result of the colonial railway expansion. The buffalo decimation is an underacknowledged but foundational aspect of “Canadian” history, with consequences that persist today. Built on Genocide will address the direct correlation between the genocide of the buffalo and the genocide of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

© 2025 Luminato Festival Toronto, All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy

|

Terms and Conditions