Who Wrote Canada’s History? The real story of first contact.

Hello everyone! In our first post

, I covered a brief overview of the pre-contact years

in North America all the way back to the end of the ice age. You have to have a basic understanding of the nations that lived here before we begin discussing Indigenous history in detail. Most important point: these lands were not empty. With that in mind, let’s look at Indigenous peoples’ first contact with Europeans.

Did you know that a few Indigenous nations had premonitions of the coming of foreign people to the continent? Specifically, Mi’kmaq, Ojibwe, and Cowichan nations all had dreams of the arrival of new people from another land. Word spread of these premonitions to nations beyond the Mi’kmaq, Ojibwe, and Cowichan and as a result, many Indigenous nations were not surprised the first time they saw a European man.

Most European colonists came from the east coast and first contact took longer for Northwest Coast and Arctic nations. During early experiences of first contact in the 16th and 17th centuries, Indigenous people were intrigued by the different tools, clothes, and items that the Europeans had. They were also frightened by firearms as they saw their great power and the power given to those who wielded them.

In spite of this, Indigenous people still had the upper hand during first contact. They knew the land, their neighbours, how to navigate, and the knowledge of the area that colonists lacked. Colonists, therefore, relied on Indigenous guides and interpreters.

Watch Who Were the Ones on NFB

This short film was created by a group of Indigenous filmmakers at the NFB in 1972 and is essentially a song by Willie Dunn sung by Bob Charlie and illustrated by John Fadden: “Who were the ones who bid you welcome and took you by the hand, inviting you here by our campfires, as brothers we might stand?”

- Reading for Kids: Rabbit and Bear Paws by Chad Solomon & Christopher Meyer

As more colonists came to the continent, Indigenous nations found their economies and ways of governance changing as a result. One of the biggest impacts was the fur trade industry. If you went to school in Canada, at some point during your education you likely learned about the fur trade. It’s unlikely that you learned the many ways that the trade impacted Indigenous lives.

Other nations like the Anishinaabek, Dene, and Innu traded as well but not as often and their networks didn’t extend as far south. Trade was not just for exchanging goods but also for maintaining alliances and relationships with neighbouring groups and nations. When opposing nations made agreements, goods were often exchanged in order to solidify the importance of the agreement and to show the respect each nation held for each other. Items traded for these alliances were often not just ornamental but useful, things like dried corn or tools. Throughout the continent, trade was an integral part of society.

Turtle Island Trade Networks Map by the Yuchi Indigenous People

- Click below to watch Watch Tkaron:to & Turtle Island: The Remarkable Indigenous Trade Networks , a talk by Bonnie Devine at Myseum of Toronto

The fur trade was quite different from the established trade networks as furs were the primary commodity (other items were traded too but the most profit could be made with fur). Additionally, the trade was not being done with traditional allies but completely new people. The fur trade changed traditional ways of life for many, including the Denésoliné, whose story is similar to others.

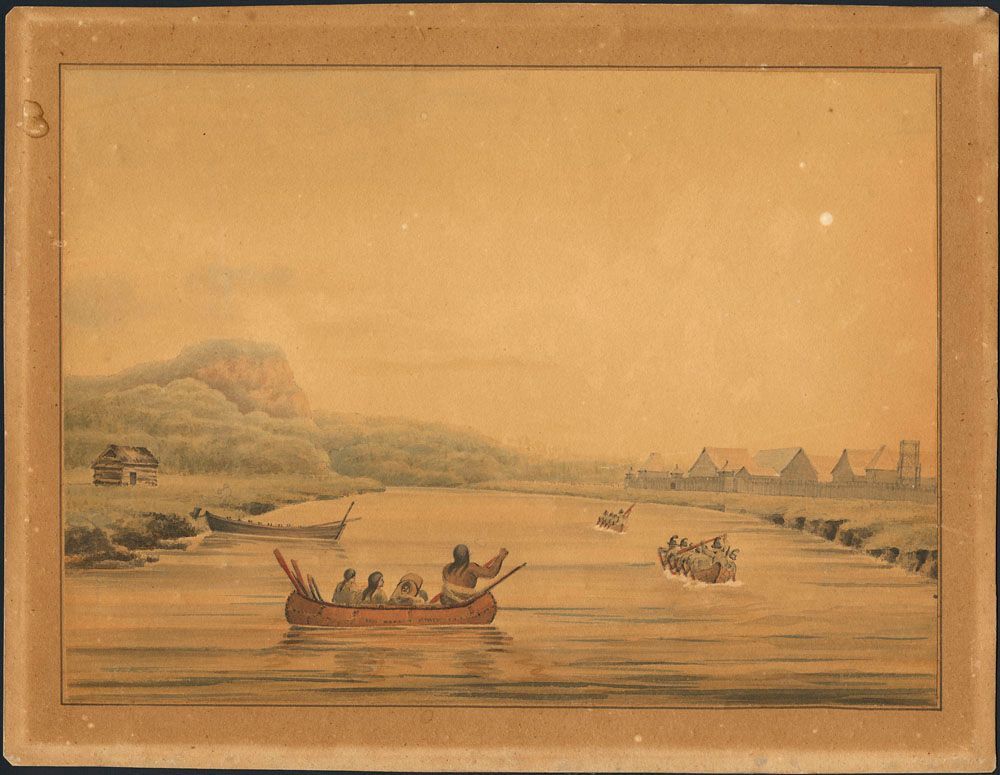

A trading post was established by the Hudson’s Bay Company along the Churchill River in 1717 within traditional Denésoliné territory. At the time beaver fur was in high demand as it was a huge fashion trend across Europe and traders were willing to pay top dollar for it. The Denésoliné hunted the desired beaver for its fur, almost to extinction. They also became middlemen for those further inland who also wanted to trade. As a result, the Denésoliné became dependent on the fur trade rather than their traditional way of life hunting and gathering.

At the time of the fur trade, many European colonists presented North America as the “New World” that was empty and free for the taking. But you know that wasn’t true. There was a large and diverse population of Indigenous peoples already here who had their own intricate and complex ways of life.

The Denésoliné did not realize that being in close contact with Europeans was exposing them to foreign diseases that their immune systems had no previous exposure to. They were devastated by a smallpox epidemic in 1781, one of many diseases brought over to North America by Europeans. With no immunity or knowledge of the disease a large portion of the population passed away. Not just the Denésoliné, but many Indigenous nations’ populations decreased because of foreign diseases brought along by colonists.

Watch The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company on NFB

Narrated by George Manuel, then president of the National Indian Brotherhood, this landmark film presents Indigenous perspectives on the company whose fur-trading empire drove colonization across vast tracts of land in central, western and northern Canada.

The damaging patterns that began in the fur trade only persisted over time. Indigenous communities made the switch to the colonial type of economy and became dependent on money rather than the land for their subsistence. Damage to the environment through things like overhunting, pollution, and land clearing only furthered this. The legacy of this damage even continues today with many Indigenous communities experiencing food insecurity and poverty. Just one example would be in Nunavut where grocery prices are around 3x higher than the average Canadian price, this isn’t just a Nunavut problem though, most other remote areas also experience this. Even if not in a remote area, providing enough food for everyone in your household can be expensive.

At the time of the fur trade, many European colonists presented North America as the “New World” that was empty and free for the taking. But you know that wasn’t true. There was a large and diverse population of Indigenous peoples already here who had their own intricate and complex ways of life.

Pictured to the left: View of the Hudson Bay Company’s Fort, Norman House, from the river Kamanistiquoia by A.B. Becher

Think about what you learned in school. Who wrote that history? Is it possible they left anything out to make themselves or what they were doing look better? That is often the case when it comes to Canadian history written by settlers. Indigenous history is silenced in order to justify colonization.

I want you to consider this when learning and thinking about Canadian history. Indigenous people were actually who helped early settlers to survive, as everything was foreign and new to them. However, settlers also brought danger, things like guns and disease were a threat to Indigenous peoples’ traditional ways of life and began to alter them. Though settlers claimed to be “civilizing” North America were they actually doing more harm than good?

There were other new systems aside from trade that Europeans brought with them that began to transform the continent. We’ll explore some of those other factors like intermarriages and Christianity further to gain a better understanding of the contact period.

Read the next post: Contact Continues: Clash and Blending of Cultures

About the Author

Mnawaate Gordon-Corbiere is Grouse clan and a member of M’Chigeeng First Nation. She is Ojibwe and Cree. Born in Toronto and raised in M’Chigeeng, in 2019 she obtained her BA in History and English from the University of Toronto.

Since graduation, she has been working in the heritage sector with a focus on Indigenous history. Her most recent project was working as a co-editor for the historical anthology Indigenous Toronto: Stories that Carry This Place

released in spring 2021.

About Built on Genocide

Built on Genocide is a large-scale installation by multidisciplinary artist Jay Soule | CHIPPEWAR, reflecting the events and policies throughout Canada’s history that have deliberately undermined and destroyed Indigenous livelihoods.

The work is influenced by the mass genocide of the buffalo as a result of the colonial railway expansion. The buffalo decimation is an underacknowledged but foundational aspect of “Canadian” history, with consequences that persist today. Built on Genocide will address the direct correlation between the genocide of the buffalo and the genocide of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

© 2025 Luminato Festival Toronto, All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy

|

Terms and Conditions