Behind Edward Burtynsky’s Photographs

Toronto photographer Edward Burtynsky captures the parts of our lives that we often take for granted. Whether it’s an untouched landscape in a corner of the Earth we’ve never seen, or refineries and factories that are the backbone of consumerism, Burtynsky’s photography casts a light on our relationship with nature and industrialization.

The world is replete with subject matter.

Edward Burtynsky

Burtynsky’s fascination with photography began with capturing the pristine landscapes of our world. As a child, road trips with his father took him to untraversed areas of Northern Ontario. Endless landscapes zipped by as he sat in cars and stared out the window. These areas of Earth, unaffected by humans, acted as reminders that we’re all temporary residents here. Today, very few parts of the world remain untouched as human progress rapidly encroaches on these spaces.

The public world premiere of Edward Burtynsky’s In the Wake of Progress takes over the immense digital screens surrounding Yonge-Dundas Square on June 11 and 12, 2022 in a fully choreographed blend of photographs and film, with a staggering musical score. Against the backdrop of the devastating effects of the COVID-19 global pandemic, Edward Burtynsky’s In the Wake of Progress challenges us to have an important conversation about our legacy and the future implications of sustainable life on Earth.

Read on for a glimpse of the images that make up In the Wake of Progress. Discover the provenance of these iconic images in the words of Burtynsky himself.

Stikine River, Northern British Columbia, Canada, 2012

Edward Burtynsky, on water:

“Over the course of the five years it took to make my Water series, and throughout the span of my career, really, I have learned a few things about water. When disrupted from its natural course there are always winners and losers. The moment water cannot find its own way back to the ocean or be absorbed by the ground, we are changing the landscape. When a stream or river is diverted, all life downstream is affected and remains altered until water returns. Insects, plants, frogs, the salamanders and countless other creatures- including people – have paid an enormous price because of our voracious appetite for water—and what we do to the earth while getting at it.”

– Excerpt from the Water series Artist Statement

Cathedral Grove #2, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, 2017

On the pristine old growth forests of British Columbia: This image depicts great rainforests under stress. The temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest coast are an incredible site of biodiversity. British Columbia, pictured here, occupies only 10 percent of Canada’s geographical area, yet the province contains more than half of Canada’s vertebrates and vascular plants, as well as three quarters of its bird and mammal species. Some of the tallest trees in the world can be found in the old growth forests of this region.

Today, 90 percent of BC’s logging occurs on publicly owned Crown lands. While less than one percent of the province’s forests are harvested annually, Vancouver Island’s primary rainforests are logged at three times the rate of tropical regions. While a visitor to Cathedral Grove on Vancouver Island may be struck by the feeling that they are in an eternally regenerating woodland, they would be wise to note that such forests are as vulnerable as they are majestic.

– Excerpt from Anthropocene

by Edward Burtynsky, Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier (Steidl, 2018)

Highway #2, Intersection 105 & 110, Los Angeles, California, 2003

Edward Burtynsky, on oil and cars : “One of my most liberating moments as a photographer came after graduating from University, when I received a grant to go and do my work. I remember starting up my Volvo and pulling out by myself on a four-month-long adventure.

When I first started photographing industry it was out of a sense of awe at what we as a species were up to. Our achievements became a source of infinite possibilities. But time goes on, and that flush of wonder began to turn. The car that I drove cross-country began to represent not only freedom, but also something much more conflicted. I began to think about oil itself: as both the source of energy that makes everything possible, and as a source of dread, for its ongoing endangerment of our habitat.

In no way can one encompass the influence and extended landscape of this thing we call oil. These images can be seen as notations by one artist—contemplating the world made possible through this massive energy force, and the cumulative effects of the industrial evolution.”

– Excerpt from the Oil series Artist Statement

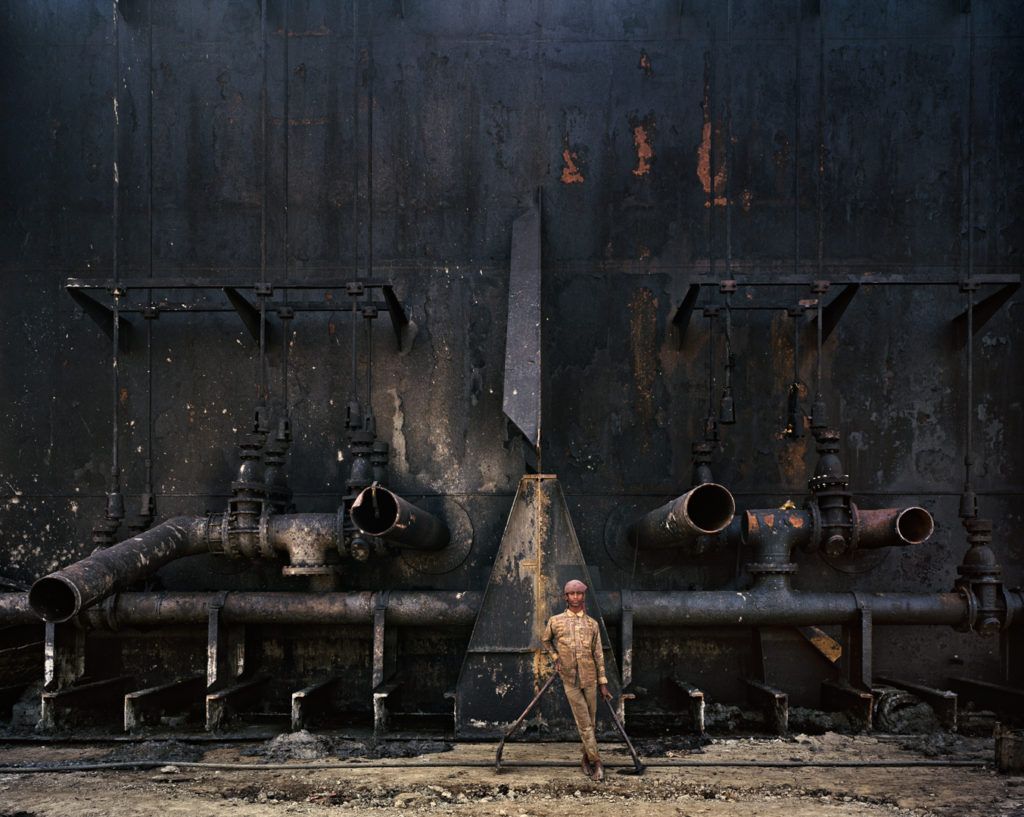

Shipbreaking #23, Chittagong, Bangladesh, 2000

Edward Burtynsky, on shipbreaking: “The remarkable thing about the process of shipbreaking in Chittagong, Bangladesh was that the workers had no technology other than a cutting torch and whatever else they could find on the boats. Everything available came in the form of motors, wrenches and cables, and then the workers’ bare hands. The shipbreaking in Chittagong still remains one of the most remarkable and unbelievable things I’ve ever witnessed. There seemed to be such a disconnect in this place, a complete disregard for human life, health and the environment. I didn’t know something like this could exist in that day and age. In many ways it felt like stepping back in time to the era of Dickens and the satanic mills, where human life was cheap. It seemed to answer the question: what does the world look like when there are no rules, no understanding of health and environmental consequences to the industrial processes they were engaged in?”

Oil Refineries #3, Oakville, Ontario, Canada, 1999

Edward Burtynsky, on refineries:

“All of the stuff that is extracted from the earth has to go through some process on the way to making the consumer goods of our culture. So, I turned to one of the first stages in the industrial metamorphosis, which is the refinery. It is an interesting counterpoint to see a mine that looks like architecture and a piece of architecture that looks organic. A refinery is clearly an architectural space but strangely inverted. Typically, a structure contains a machine, but because the refinery builds up a lot of heat and expresses gasses, the internal workings of the machine are on the outside. I don’t think when they build a refinery there is an overall vision of how it’s going to be constructed. They simply want to find the most efficient machine that does the task and with that premise the structure unfolds. It was very interesting to me to work towards finding a way to visually reconcile that complexity.”

– Excerpt from interview with Michael Torosian, as seen in the Manufactured Landscapes

book.

Densified Scrap Metal #3a, Hamilton, Ontario, 1997

Edward Burtynsky, on mining: “I wanted to build a branch off the main core of my work and not locate it strictly within the realm of the landscape. I wanted to find the next place.

I considered that there is primary mining – we go to the land and we blast and we take ore – that is the initial extraction. And then there is the relatively modern phenomenon of recycling – the source for the secondary level of extraction. This is the “urban mine.”

We’ve never stopped taking things from nature. Even the act of taking from the earth is natural since we are not outside of nature. What is different today is the scale. Current society is searching for a way to come to terms with that taking from the earth. Recycling is one way we can put a stop to a certain amount of damage to the earth. This material comes from and collects around urban centres in large recycling yards. These yards are like secondary mines.”

– Excerpt from the Urban Mines series Artist Statement

Aqueduct #1, Los Angeles, California, USA, 2009

Edward Burtynsky, on water

: “Human ingenuity and the development of its industries have allowed us to control the Earth’s water in ways that were unimaginable even just a century ago. While trying to accommodate the growing needs of an expanding and very thirsty civilization, we are reshaping the Earth in colossal ways. In this new and powerful role over the planet, we are also capable of engineering our own demise. We have to learn to think more long-term about the consequences of what we are doing, while we are doing it. My hope is that these pictures will stimulate a process of thinking about something essential to our survival, something we often take for granted—until it’s gone.”

– Excerpt from the Water series Artist Statement

Don’t miss Edward Burtynksy’s In the Wake of Progress

The public world premiere of renowned Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky’s In the Wake of Progress takes over the immense digital screens surrounding Yonge-Dundas Square on June 11-12, 2022 in a fully choreographed blend of photographs and film, with a staggering musical score.

Get an inside look at In the Wake of Progress

© 2025 Luminato Festival Toronto, All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy

|

Terms and Conditions